|

fundekals Research

Mosquito Engine Cowlings - More Than Meets the Eye!

by Jennings Heilig

HyperScale is proudly supported by Squadron

Looking back through the blur of history nearly 75 years on, it is difficult to fathom just how revolutionary the de Havilland DH.98 Mosquito was. When she first flew on 25 November 1940, the Mosquito represented a quantum leap forward in bomber design. Not only was she completely lacking in any form of self-defensive armament, but her forward-thinking designers had endowed her with a level of aerodynamic and mechanical sophistication unrivaled to that point, and some time afterward. The fact that Rolls Royce’s magnificent Merlin engine had matured as a viable powerplat at preciesly the right time for de Havilland gave the Mosquito’s designers the absolute perfect power package for their sleek design. With her wooden construction and resulting super smooth aerodynamic surfaces, the Mosquito proved from the start that she was a thoroughbred chomping at the bit.

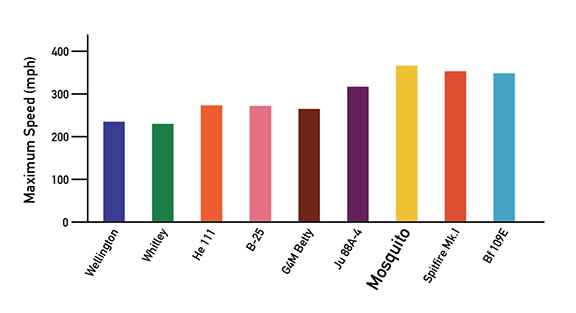

Almost immediately after its first flight, the Mosquito’s stellar performance turned a lot of heads within the RAF, the Air Ministry, and not a few in foreign air arms. She proved to be faster than even the vaunted Spitfire, then seen as the best, fastest, and most formidable fighter in the world. The ‘Mossie’ easily left it and every potential German foe in the dust, leading to the Mosquito’s initial use as a high speed reconnaissance platform. Able to fly higher than any Luftwaffe anti-aircraft weapon could reach, and faster than any Luftwaffe aircraft could fly, the Mosquito got in, got the job done, and got out.

A comparison of the top speeds of Mosquito contemporaries, as well as the Spitfire and Bf 109.

As with any radically new technology, the Mosquito suffered its share of teething troubles. Ongoing issues with horizontal stabilizer flutter eventually led to extended engine nacelle aft ends, although this problem was never completely solved. The extremely tightly cowled Merlins and their innovative exhausts were another source of problems, and one which de Havilland continued to work on.

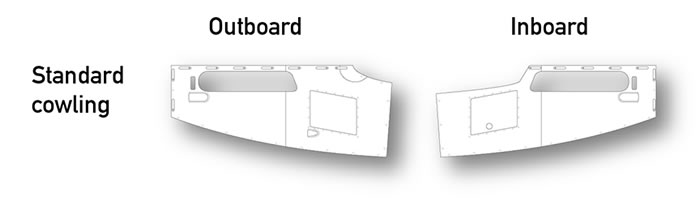

The Mosquito was designed to accept a shrouded exhaust to reduce glare, and thus make the aircraft more difficult to spot, particularly at night. However, the exhaust shrouds robbed precious performance due to their increased drag and a reduction in engine output related to exhaust stack design. de Havilland tried a number of variations on the exhausts before settling on a five-stub setup that became the production standard. Of note are the rounded opening for the exhaust stacks, the small vertical rectangular opening forward of it, and the small intake just below the exhaust opening. Due to the geometry of the wing, engine cowlings, and the leading edge of the radiators on the inboard side of the nacelles, it was not possible to fit six individual exhaust stubs on both sides. To allow for a standard setup on each side, the #6 exhaust was routed forward to join with the #5 stub. While this allowed the exhausts to fit into the physical space available on the inboard side, it was less than ideal from a performance standpoint.

In a never-ending quest for more speed, sometime in late 1941 or early 1942, de Havilland began to experiment with an asymmetrical unshrouded exhaust setup, with the standard five stubs inboard and six individual stubs outboard. While unusual, it was found that this asymmetrical configuration, using oval section outlets and six individual stubs on the outboard side, netted a whopping 10-14 mph of additional speed at the top end of the performance curve. The Mosquito was already lightning fast, and although the element of concealment provided by the shrouded exhausts was lost, it was felt that the additional speed more than offset any disadvantage incurred.

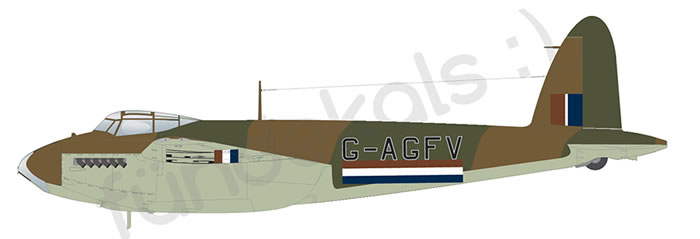

We have not been able to determine conclusively how many Mosquito bombers received this unique asymmetrical exhaust modification, but we do know that several did. Notably, the B.Mk.IV transferred to BOAC in December 1942 (DK411, registered G-AGFV) featured it, as did DK290/G, the aircraft used at A&AEE to test the Highball spherical bomb, plus several standard B.Mk.IV bombers issued to regular RAF squadrons.

The modification to the cowling side panels for the six-stub exhaust later became the standard one used on the longer nacelles of the two-stage Merlin-powered bombers. The two-stage supercharger necessitated moving the entire engine forward by 10 inches, providing room for a six-stub exhaust on both the inboard and outboard sides.

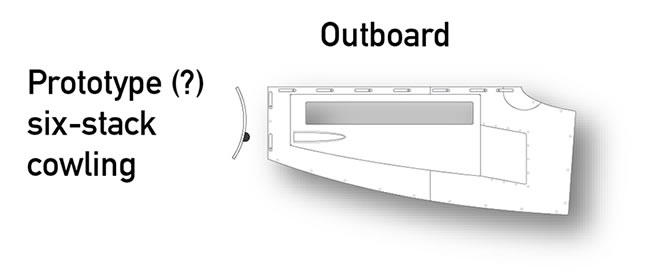

We have identified what we believe to be a prototype installation as seen here. We do not know the identity of this aircraft, but it clearly has standard cowling side panels, with a new piece of skin riveted in place containing the larger, more rectangular opening for the six-stub exhaust. Also note that the small vertical rectangular opening just forward of the exhaust opening is now gone, as is the small intake just below it. A new air intake scoop, much longer and more tapered than before, replaces it. On this prototype, this intake appears to be a simple stamped sheet metal part with a “U” cross section.

The prototype asymmetrical cowling. Note the riveted-on skin panel and the relatively simple “U” shaped intake below it. (IWM)

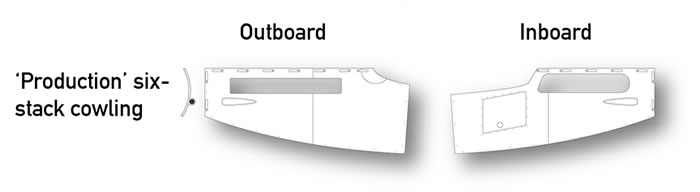

Again, without knowing exactly how many Mosquitos received it, we believe there was a “production” version of the side panel as shown here. There is no evidence of riveted-on skin, and it appears these panels were fabricated specifically for this configuration. Note that the small intake below the exhaust opening is now a more complex shape, with a fully circular opening that stands an inch or two proud of the skin, reminiscent of a Bf 109F/G supercharger intake. This same item appears on the inboard cowlings of the modified aircraft as well.

To our knowledge, this cowling/exhaust setup was only seen on bomber Mossies. We have yet to find any evidence it was ever applied to any of the fighter or fighter-bomber variants.

Mosquito PR.Mk.IV DZ411/G-AGFV of BOAC seen at Hatfield prior to delivery in December 1942. Note the six-stub exhaust and ‘production’ air intake scoop. (IWM)

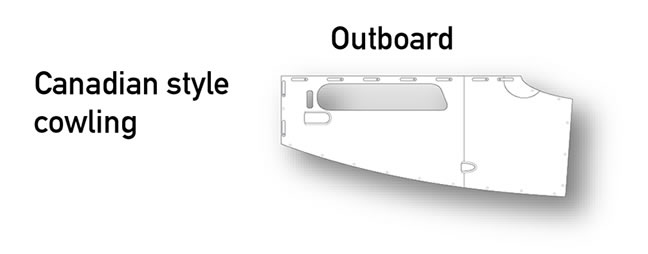

As a side note to this story of Mosquito cowlings, we discovered that Canadian-built Mosquitos, all of which used the American Packard-built Merlin, featured yet another variation of the cowling side panels. While as far as we know, all single-stage Canadian Mossies had standard five-stub exhausts, the trapezoidal panel at the aft end of the side cowling panels was missing, and the panel lines and the small intake scoop were in a different location. This illustration shows the Canadian style panels.

Close-up of the cowling side panel on de Havilland Canada F-8-DH, 43-34960 (a modified B.Mk.XX) powered by a Packard Merlin. (NASA)

Look for our forthcoming fündekals 1/32 decal for BOAC’s six-stack Mosquito PR.Mk.IV, G-AGFV!

There is undoubtedly much more to be discovered about this amazing airplane. We can highly recommend three books to round out your Mosquito reference library:

1. “Mosquito,” by C. Martin Sharp and Michael J.F. Bowyer (1967, Faber and Faber, Ltd)

2. “de Havilland Mosquito: An Illustrated History, Vol. 1,” by Stuart Howe (Crécy, 1992)

3. “de Havilland Mosquito: An Illustrated History, Vol. 2,” by Ian Thirsk (Crécy, 2006)

Copyright 2015 by Jennings Heilig

Page Created 2 September, 2015

Last Updated

2 September, 2015

Back to Reference Library

|

Home |

What's New |

Features |

Gallery |

Reviews |

Reference |

Forum |

Search